For any of you that have toiled on a diamond or football field somewhere with me know that Left Field became my house after leaving center field and that I called the shots in the huddle. On scores of fields with several teams I have been known to yell give me work……or “gimme work”. My, Dad, Reed Hoeg, was a wounded veteran and a victim of child abuse. With the resultant PTSD, I remember him teaching me about responsibility from a team perspective with high expectations having to go down with your team. It is your ball to get…. both in hardball and football “if it is up there and yours; you better grab it”. A labor of love and competition. I learned how to just turn and run and know where the ball was going. I better have for others counted on you. This was how Reed operated. He hit me fungo, threw me passes, took me bowling, etc and we worked. Clear goals and good effort. Your effort was an indicator of your values. Your values were to be the same for all people.

Growing up with Reed was an extremely raucous exciting and cultural excursion. You would walk places out of practicality, with your life endangered because it was “good to see it all.” We went through a very downtrodden slum to see a co-worker’s son play football on the other side of town. There was open hostility directed throughout at us but we made it none the worse for wear, mind you this was a good five or six miles and I was eight. There was always an edge and a “high end” payoff in stimuli for Reed. He took 4 young kids to Montauk, Long Island from Brooklyn by Bike. It was onward and enjoy the reward. Nothing felt better than the ocean followed by the pool when you worked hard to get there and earned the privilege.

Hiking, Films, Sports, Food, “Window-shopping”, and acute awareness of things going on around you all in the name of feeling your way and learning was the thing. We would bike to Manhattan over the Brooklyn Bridge, grab a bite at Manganaro’s Hero Boy and he would take pride in showing me the ropes on the streets. I was between 9 and 12 I feel that he was trying to tell me something about people. It infuriated him that there could be people treated like animals, or any hint of racism or bias; it incensed him. I got it. People are not to be treated poorly and you must respect every single person and work with them. He could not stand racism, the hypocrisy of poverty, and the concerted effort to have segregation and learned hopelessness. Is that left leaning?

So today we are into the last days of Obama and await the Trump term in office. I know my Dad would have been so about Obama but not any more than any other President aside from the obvious history and knowing that he would be up against it. He did not expect miracles and the poor have stayed poor. Trump said some things that Reed Hoeg would have chewed up and spit out. Calling out minorities and for “law and order” and stereotyping people by ethnicity and location would be devastating news for Reed. Trump exposing the fact that middle America felt abandoned; their perception, creating votes for Donald J. would have been pinned out be my Dad long before the media and polls screwed up. I am quite certain that if there was a way to prevent poverty, war, racism, and inhumanity in the form of protest, that Reed would be there ready to work.

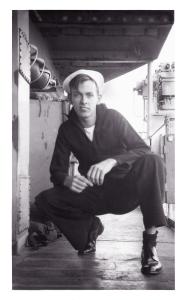

He pulled me in a red wagon in a protest against the Viet Nam war in Washington D.C. in the 60’s. The protesters were confronted by groups that claimed that veterans were being disrespected by their chants and anti-war sentiment. Reed had a way of speaking in that yelling always meant all was fair in love and war and you were safe. When he spoke in a whisper you would just get it over with and pee yourself. Well he could no longer take it and said poignantly and calmly “I AM A VETERAN” and walked on to the new-found silence of the slack jawed naysayers. My Dad felt it was his responsibility to do the work and whatever it took to get it done. Own the responsibility, what it stands for, and run with it till you are stopped. In the Korean war, he lost friends, killed in front of him, and saw a lot of people die in morbid ways. He proudly served and got injured severely, spent a year in the hospital, and was scarred for life and refused all benefits in a stoic patriotic fashion. He worked hard for his peers to fight and stay alive. At times not hard enough;,crushing him with despair.

A truly loved man at work and within a year of his death I got a call from Reed’s company. The person told me they had one paycheck left and they said “we don’t want to give it to that bitch” meaning my mother, who lived life like an odd and bad wanna be soft core porn Cagney flick in a two-bedroom apartment, with my sister nine years my junior, and asked if they could mail it to me. Reed had worked at Louis Dreyfus for 40 years and was never absent or late a day. Well, he deserves recognition on this day and with our future on hold in America. I know where he would stand on things and I would be proud to be beside him. Knowing that if things were to about to go down we both would be thinking “gimme work” or hauling it in for the good guys. First to the finish line leave no one behind.

Thanks, Dad, for fighting for this country that you so desperately wanted to be the same for everybody. Thanks for letting me know what I needed to know to show appreciation and love and not hate. In later years helping me maintain a home and giving my kids a shot in the arm for tuition. You must have been a terrific soldier. You were a fantastic friend and a Dad for my formative years, and “grandad” to my kids and for loving my wife; Patti.

“You have to be in position to throw , when you catch the ball, with a runner on third base, less than two outs, and on a pop fly to the outfield and no one else on. You have to come up throwing; nail that fuck.” -Reed Hoeg and millions of others. I died for the moment and I must tell you that making that catch and throw is better than most things. Nothing better than the ump making that call and if it was the third out running in with your men and high fiving. Got work, used gun, and zap. Certainly a fist pump for Reed Hoeg.

I relish seeing to it that my loved ones are in a good place and trying to making the world a better place for others. I know Reed is with Gil Hodges and his friend Bob Katims stuck on 1948 and the argument about no greatest player until blacks were allowed and agreeing with it. “Yeah sure ” knowing that he recognized, in any sense of the word, in fact it was deserving of a sock on the nose.

“Let’s see what he does”. OK Dad…

“Gimme Work”…..l

Reed Hoeg died in January 2002 at the age of 71 of a broken heart. The only thing that could kill him.